This article is part of a series exploring how the church responded to significant insights, movements, and events in the 20th Century, and how these have shaped where we are today.

“The social gospel is the old message of salvation, but enlarged and intensified. The individualistic gospel has taught us to see the sinfulness of every human heart. . . . But it has not given us an adequate understanding of the sinfulness of the social order.”

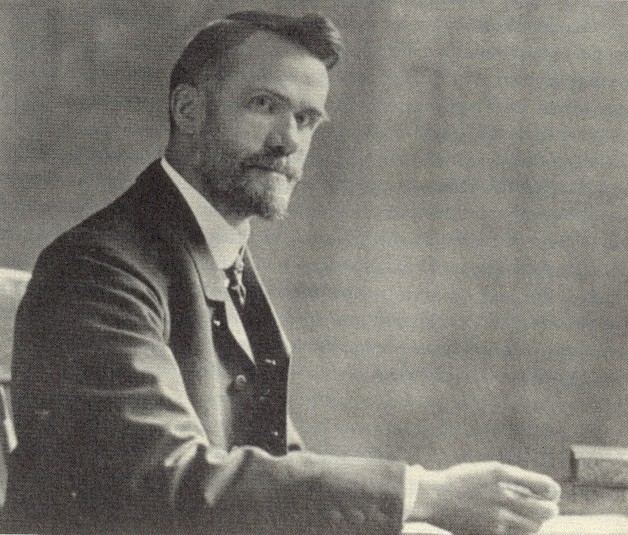

Walter Rauschenbusch

Most of our churches in the 21st century have some kind of outreach ministry to help people in need. We believe that it is central to our Gospel proclamation. In the Anglican Church of Canada, in our baptism, we promise both ‘to seek and serve Christ in all persons, loving our neighbour as ourselves’ AND ‘to strive for justice and peace among all people, and respect the dignity of every human being.’ These are no longer controversial statements. Why is that? Part of the reason is the ministry of Walter Rauschenbusch (1861-1918), the founder of the Social Gospel Movement.

A Challenging Ministry

Walter Rauschenbusch was a new pastor in 1886 when he started at Second German Baptist Church in the neighbourhood of Hell’s Kitchen, New York City. It was called Hell’s Kitchen for reason. The neighbourhood was filthy and neglected, a place of poverty, crime, disease and hopelessness. It was a hard first calling for a new pastor! He later wrote, “Oh, the children’s funerals! they gripped my heart. That was one of the things I always went away thinking about—why did the children have to die?”

His problem was that he had been taught to preach a Gospel of personal salvation: that Christ died for your sins, and if you put your faith in him you will go to heaven. Rauschenbusch started to wonder if the Gospel had anything to say to his parishioners other than to wait for heaven. The churches were giving charity, but he felt that there had to be more. He started to think that the church had a responsibility actually to change the social conditions people were living under. But he wasn’t sure of the theology behind it.

The Gospel Through New Eyes

As he pondered this question, he started to read the New Testament with new eyes. In 1891, he found what he was looking for. Of course, it had been there the whole time. He rediscovered the central message of Jesus in the Synoptic Gospels: The Kingdom of God. The Kingdom of God in the New Testament is a vision of a new world and a new creation.

For Rauschenbusch, this theme was all encompassing. It captured both personal faith AND social transformation. It connected the church to the world in a powerful way, one that had been neglected and forgotten over the centuries. He published his insights in A Theology for the Social Gospel and started lecturing widely. For three years after its publication in 1907, his book was a best seller. Harry Emerson Fosdick said that the book “struck home so poignantly on the intelligence and conscience … that it ushered in a new era in Christian thought and action.”

The Rise of the Social Gospel Movement

Rauschenbusch’s message resonated strongly with a population of Protestant Christians eager to make a difference in the world. From his and others’ ideas rose the Social Gospel Movement, which had a significant impact in the early 20th century. Social Gospel activists were concerned not only with preaching the Gospel, but with working for labour reforms such as the abolition of child labour, a shorter work week, and a living wage. Many of Rauschenbusch’s ideas found expression in the 1930s with the rise of the labour movement and the New Deal under President Franklin D. Roosevelt. (Read more about the Social Gospel’s influence on Roosevelt here.)

The Social Gospel Movement Still Forms Our Theology

I want to help us in the 21st century understand that our faith comes from key moments that happened in the 20th century. Although the Social Gospel movement peaked in the mid-20th century, these ideas still form the theology of our Mainline churches. At the beginning of this reflection, I quoted two promises that form the backbone of our understanding of our Baptismal responsibility. Without Walter Rauschenbusch and the others in the Social Gospel Movement, we would not have this understanding of baptism. They added to our insight into the Gospel of Jesus Christ.

There were Canadians in the Early Social Gospel Movement – one example: Salem Bland https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Salem_Bland

And yet. I can’t help believing that our mainstream social gospel theology is one reason that the mainline churches are fading. I mentioned William Jennings Bryan in an earlier comment. He really believed that if John Scopes was permitted to teach evolution, the faith would start to decay, and in this he was wrong. How then could all the noble hopes of devout social-gospel Christians do harm? I was a young man when, in the sixties, idealistic young pastors started using the Church as an instrument to combat racial discrimination in Canada and the US, and to try to halt the Vietnam War, both noble causes. The trouble started with the almost-infinite capacity of our popular culture to distort and to vulgarize. I still recall with a shudder the efforts of Hugh Hefner and his “Playboy” magazine—taken with absurd seriousness in the sixties—to try to enlist “liberal Christians” into the cause of “swinging, liberated” secular life. The problem was that a lot of influential Christian ministers and religious thinkers couldn’t wait to be enlisted. They wanted to be more “relevant,” and “with it.” I lost track of all the “Playboy interviews” in which earnest theologians babbled on about “situation ethics,” and the usefulness of really good sex in building a relationship with the Divine. The Kama Sutra! The magazine was full of articles showing Hefner puffing his pipe, in deep conversations with Protestant grandees who had spent a week in the Playboy Mansion in Chicago. I used to wonder what the various Reverends did when the live-in Bunnies rattled their doors at 3 a.m. Were the Mrs.Reverends along on these junkets? I believe even men as morally heroic as the Berrigan brothers got their Playboy interview. And of course it wasn’t just hustlers like Hefner who were the tempters. The two great social movements of the age were the hippie phenomenon and the anti-war movement. I was a teacher at a Christian high school in the early seventies, and I encountered too many aging clerics who were determined to be seen as “with it.” Of course they believed in peace and love (maybe not free weed and free sex.) They’d appear at our chapel services as guest speakers, what was left of their greying hair scraping their shoulders, assuring the students that Jesus was “groovy,” that he was “where it’s at.” And the students, who might have wanted some timeless wisdom, were laughing at them. And then there was the anti-war movement, in which many good Christian men and women took part, and sometimes went to jail. The problem there was that the student organizers of the protests couldn’t have been more contemptuous of religion in any form. I knew some of the organizers, and they regarded their religious allies as, in Lenin’s phrase, “useful idiots.” The result of all this well-meaning stuff was that by the late seventies the whole mainstream Christian enterprise in Canada and the US had, in the words of a conservative Christian judge I knew, gone “seriously off-message.” I’ll say. When I started exploring Christianity in the late eighties, I was startled to encounter a young mainstream Protestant minister who liked to refer to policemen as “pigs,” and another who in the course of a sermon on the parable of the poor man at the rich nan’s gate informed us that God was a myth and encouraged us to give him money so he could send it to the rebels fighting US imperialism in Central America. (They weren’t Anglicans.) The trouble with all this—and its equally idiotic mirror image, the Franklin Graham fundamentalists who worship Donald Trump—is obviously that it’s POLITICS. Not only does it infuriate the opposition; it makes everyone else wonder why you’d go to church and worship some God when it’s all simply about shouting dumb head political slogans. I was horrified when the Primate of the Canadian Anglican Church stated a year or two ago, in the course of a diatribe about the death of Colten Boushie, that the RCMP deliberately left the dead body lying on the ground in the rain for 24 hours. I tried to verify this and to the best of my knowledge it is untrue, and the Primate was acting as a very non-useful idiot when he said it.

Thanks for taking the time to comment Dave. I appreciate your thoughts. I think I would say two things. First, this article is not the end of the story. Roger Olson argues that the first world war set back the optimism of the social gospel movement. At the beginning there was in some forms of it an optimism of the ability of humanity to move forward from progress to progress until it all came out as the kingdom of God. WWI set that back, but still could be seen in the 20’s and 30’s, but after WWII, liberal Christianity went on the defensive. As well, with the rise of patriotism for WWI a lot of idealists found they chose nationalism over idealism. Rauschenbush in 1918 wrote: “since 1914, the world is full of hate, and I cannot expect to be happy again in my lifetime.

Second, if the social gospel means just social improvement, then something central is missing. Christianity is not just about social change, but also spiritual salvation from sin and death through Jesus Christ and the eschatological coming of the kingdom of God. The point I was trying to make is that the gospel is not just spiritual salvation. There is a concrete material aspect as well. We might not make the world into the kingdom, but we need to care about the world, to do justice because God cares about justice, and the good deeds that we do now will matter in eternity.

I agree with you. The Christians of the sixties should have said to the hippies, “We agree with you about peace and love, but we don’t get that from Woodstock, we get it from our living God. Come to Him and you can have peace and love every day of your lives.” They should have told the anti-war movement, “We will sit with you on the railroad tracks to block the troop trains, not because of Marxist teaching but because God commands it.” And they should be saying that now to the left and right wing fanatics who want to enlist them as allies. Church leaders are always too ready to embrace popular political trends—today maybe embracing left wing causes, at some future time (as they often have in the past) banging the drums for some stupid war. These days the church leaders are I think afraid that if they are not seen as “relevant,” what’s left of Christian faith will disappear. I wonder. Everyone is lost and searching now. It may be that a lot of people would be attracted to a group of people who had eternal allegiances, and didn’t adjust to whatever madness is going on. But I agree that we have to take a stand on social issues. God does command it.